My Aphantasia Revelation

The revelation

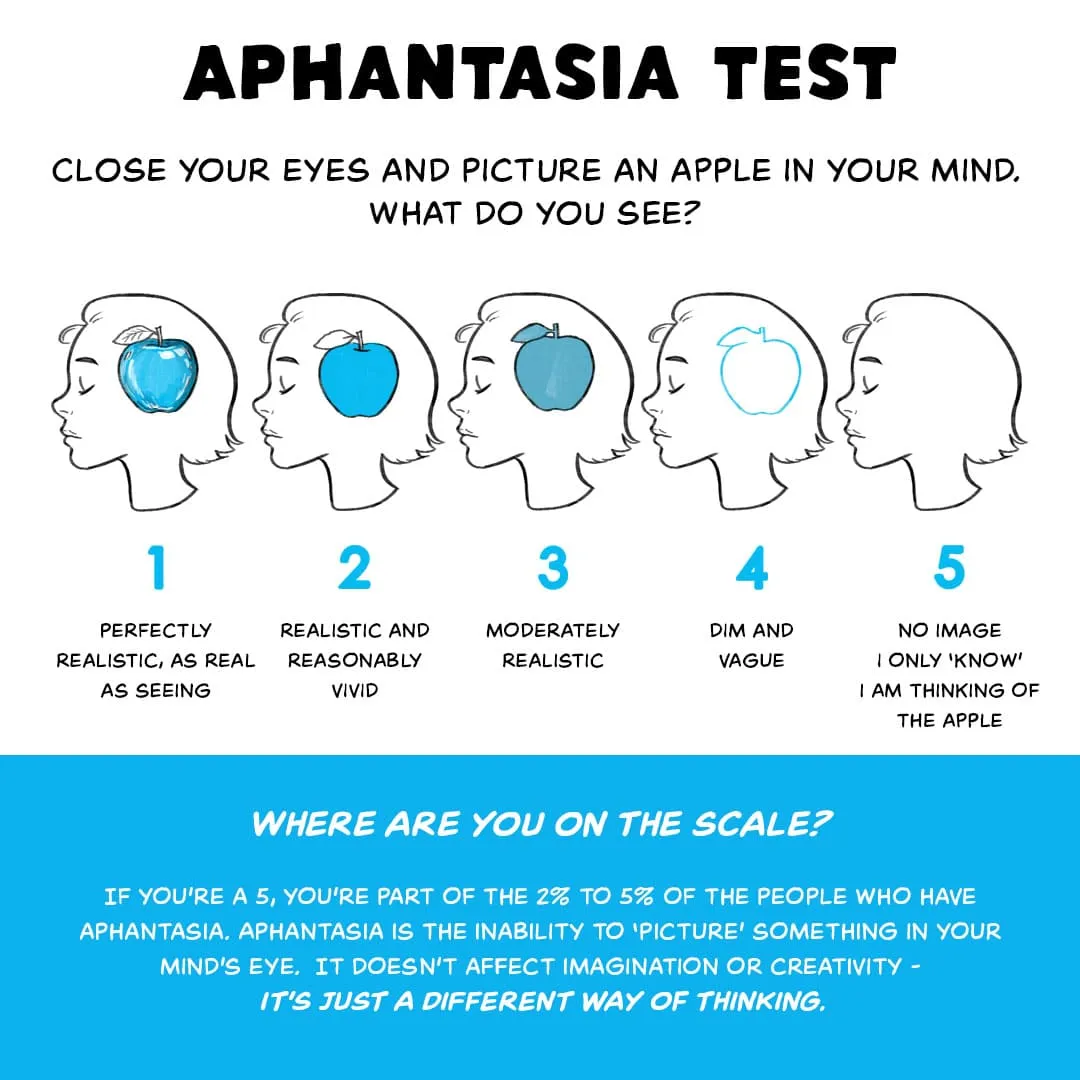

I discovered I have Aphantasia (the inability to create mental images in your mind) at the start of May this year. I’ve come to terms with it since finding out. I was living ignorantly in bliss for three decades… This all began after my wife innocently showed the image below:

She was around a 1 while I was a complete 5 on the scale. No matter how hard I tried to visualise the apple, it was just complete darkness in my mind. This was a complete surprise to both of us. I then asked her, “When I say these words: ‘there is a dog on the bed’. Do you see something?”. She confirmed that she did see the dog on the bed in her mind’s eye. I was floored. I couldn’t fathom how the majority of the world has this ability to conjure images in their mind at will and like magic 🤯. I was part of the 2-5% of the world without the ability.

I frantically researched everything I could about aphantasia and other people’s experiences with it. The word “aphantasia” is derived from the Greek word “phantasia,” meaning “imagination,” and the prefix “a-,” meaning “without”. It was coined somewhat recently in 2015 by Dr Adam Zeman after he encountered a patient who had lost the ability to visualise. Looking further back, there was even a case described in 1880 by Francis Galton. Many of the stories I found hit close to home. A common story was failing to complete meditation exercises where you imagine you are relaxing on a beach etc. Another realisation that many had was “counting sheep” relies on seeing them in your head.

Scientific research into it is still in its early stages. Most of what we know comes from small scale studies and personal accounts, leaving a lot of unanswered questions about how it affects thinking, creativity, and memory.

I eventually came across the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ), a well known tool for measuring the vividness of mental imagery. It was originally developed in 1973 by British psychologist David Marks. It contains 16 questions, each asking you to rate how vividly you can picture a specific scene on a 5‑point scale:

-

No image at all, I only “know” I am thinking of the object

-

Dim and vague image

-

Moderately realistic and vivid

-

Realistic and reasonably vivid

-

Perfectly realistic, as vivid as real seeing

Researchers have used the VVIQ to break down the population into distinct categories based on their scores (these vary across studies):

- Score = 16 - Aphantasia: Absence of visual imagery (~2-5%).

- Score 17-32 - Hypophantasia: Dim or vague visual imagery (~3%).

- Score 33-74 - Typical Range: Most people fall here; the median VVIQ is ≈ 57. (~90%).

- Score ≥ 75 - Hyperphantasia: Exceptionally vivid, photo-realistic imagery (~2-6%).

I scored 16, the lowest possible score and that strongly suggests I have aphantasia. Note: the VVIQ isn’t a medical diagnosis; it’s just a handy self assessment of how vivid (or not) your mental images are. Feel free to try it yourself by clicking the button below. (I used the version provided by the Aphantasia Network)

The VVIQ

Disbelief

I couldn’t believe that ‘Picture this’ was not just a metaphor and that most people actually see images in their minds when they hear this phrase. Some other phrases we use hint at this ability too, such as:

-

I couldn’t get those images out of my head / I can’t unsee that - after seeing something memorable or shocking

-

Just picture the crowd naked - advice given before giving a speech to ease nerves

-

Imagine you’re on a beach - common in meditation or relaxation exercises

-

Let me paint you a picture - when describing something vividly to someone

-

Take a mental picture - when you want to remember a moment clearly

I just thought they were figures of speech this whole time. I never questioned what they actually meant…

An eye opener was realising when people are telling stories that most listeners are forming a mental image of the story in their mind. I would follow along the sequence of events and other details, but could never picture anything. I do love listening to a good story regardless.

I also figured that reading a book must be like watching a movie in some people’s heads too. When books are overly descriptive it can get lost on me but I can appreciate a good narrative. A while ago, my wife told me that the characters in a movie based on a book she read were not quite how she pictured them in her head. I totally understand what she meant by that now!

I also started quizzing friends and family around their visualisation ability. Everyone was on different levels of the scale and it was interesting to see their perspective. My brother who has vivid mental imagery had a hard time believing that I could not visualise anything at all. His words were along the lines of ‘You have to want to visualise it’… I could try and visualise an apple for a year straight and still have darkness in my mind.You really don’t know how people think unless you ask them.

I’ve also learnt people can hear their own thoughts and imagine other senses such as sound, smell, taste and touch, all of which I lack. The mind is fascinating.

How do I think?

I think purely in concepts. When I think of a dog, I get a feeling of knowing what a dog is conceptually. I know its attributes such as:

- animal

- furry

- four legs

- two ears

- tail

- barks

- sharp teeth

These attributes are baked into my understanding of what a dog is. So I never have to think of the attributes separately. The dog is like a cake with the attributes as its ingredients. A visualiser like my wife will see an image of one of our Chihuahuas if she thinks of a dog.

If I think of a ball on a table and someone pushing it off. I can conceptualise the scene and what would happen logically:

- ball is sitting on table

- person walks up to table

- person pushes ball

- ball rolls off table

- ball starts falling to ground

- ball hits the ground

Like the previous example, this would be baked into the single thought and knowing feeling.

A visualiser will create the image and add details like what the person looked like, the size, shape and colour of the ball and the table, sometimes even details of a room that the ball would be in.

When it comes to drawing, I also rely on facts and concepts. If I were to draw a circle I have to conceptualise it. I know it’s a round shape with no corners and all points are equal distances from the centre. I just draw it based on my understanding of what it is. It’s the same with drawing people, animals, trees, buildings, cars and other objects.

Do I Dream?

I do dream, and my dreams are visual too. Everything looks like the real world, just in a hazy, dream like state. Because the visuals are involuntary, they seem to bypass whatever block prevents me from picturing things when I’m awake. It’s like my brain is capable of generating imagery, it just refuses to do it on command.

Do I have an imagination?

I do have an imagination, but it’s not visual. I can still think of ideas, concepts, stories and characters. I think some would say I have a wild imagination.

I conceptualised this scene below for this blog post:

Donald Trump is at a preschool trying to teach the kids how to put a series of shapes through the correct holes in a shape sorter. There are only 3 shapes, a triangle, a square and a circle. He is being serious in his demonstration, but he keeps putting the wrong shapes in the wrong holes and the kids are laughing at him. He is getting frustrated and finally says in defeat, “It’s easier being the president than this!”.

I can’t visualise it in my mind. I can’t see Donald Trump, the preschool, the kids or the shape sorter. I still understand the humour in the scene based on the absurdity of it all. It would be nice to see it though!

Advantages and Disadvantages

I don’t see many disadvantages with Aphantasia. If I had never known about it I would have kept living my life the same. My life is still the same after discovering it anyway! It’s never been a hindrance to me in my daily life. I just think slightly different to most people.

I do wish I could picture friends, family and pets in my mind, but I can still remember them and think of the good times we have had together. All of my memories are non visual so it would be nice to be able to visualise them. I’ve been taking more pictures and videos to store these memories now.

I think my aphantasia helps with problem solving as a software developer. For me, understanding concepts, logic, and relationships matters more than visualisation. Software systems are complex and mostly abstract. I imagine trying to picture one in your head can only go so far.

People with Aphantasia

It’s encouraging to see so many successful, creative people with aphantasia. Their achievements prove that a lack of mental imagery doesn’t hinder creativity. They include:

- Ed Catmull Co-founder of Pixar and former president of Walt Disney Animation Studios.

- Blake Ross Co-creator of the web browser Mozilla Firefox.

- Glen Keane Animator, author, and illustrator, known for his work on Disney films like The Little Mermaid and Aladdin.

- Craig Venter Biotechnologist and businessman, one of the first to sequence the human genome.

- Lynne Kelly Author and science writer, known for her work on memory and oral traditions.

- Penn Jillette Magician, entertainer, and one half of the duo Penn & Teller.

- Mark Lawrence Bestselling fantasy author known for The Broken Empire trilogy.

- Richard Herring Comedian, writer, and podcaster.

Conclusion

Discovering that I have aphantasia has been a journey of self discovery. It has helped me understand how I think and process information. I’ve learned to appreciate the way I think and the unique perspective it gives me. It’s given me new insights about how diverse our brains truly are. We’re all wired differently and that’s exactly what makes us human. That’s something to celebrate! 🥳